What makes so many of us queue for a new iPhone on the day of its premiere? Why should perfume manufacturers buy expensive licences for the use of the Ferrari symbol on their products? And how can you take advantage of the answers to these questions?

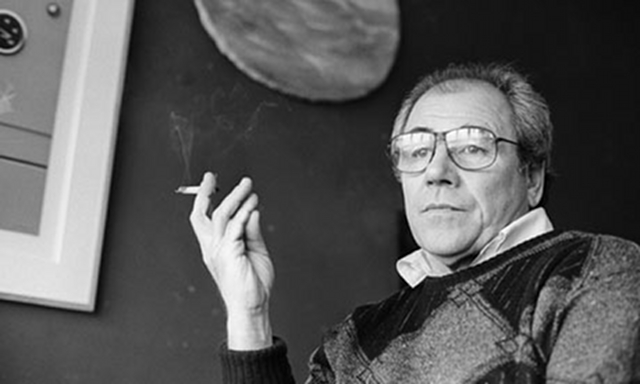

You could think that consumers, when buying goods or services of all sorts, aim to satisfy their objective needs. Following this line of interpretation, we acquire a vast array of staple goods like food, clothes, necessary equipment etc. However, almost 50 years ago, the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard published three books, in which he seems to openly challenge this supposedly commonsensical assumption. Read them carefully and you will find lots of valuable advice which can strongly affect your perception of branding and the selling process.

1. Consumers are not looking for just sweet beverages – they are looking for Coke!

According to Baudrillard, what we buy today are not products but brands in the broadest sense of the word. If we were to rely solely on the analysis of the practical value of acquired goods, we would not be able to account for the deep divisions between those who favour Samsung over Apple, Coca-Cola over Pepsi or McDonald’s over KFC. All these companies provide a similar range of services and goods of comparable characteristics and similar standard, with a matter-of-fact analysis of objective data showing differences only in the minutiae.

Hence, what really matters is not the mark, but the brand and all that it communicates. If we want our product to sell well, it must be very straightforward about who it is supposed to sell to and what it communicates. What the product is really like is a matter of secondary importance compared to how it is perceived.

2. Our buying decisions are inextricably connected with our self-perception and what lifestyle we have chosen to pursue.

Naturally, hardly anyone will openly admit that they have bought a car or a computer for its brand. On the contrary, many will honestly say that they are not bothered by brands. Baudrillard had a very clear understanding of the issue – that is why he tended to write about ‘sign’ rather than ‘brands’. Let us imagine two people wanting to have something to eat at lunchtime. One of them will order fish to go with chips while the other will opt for, say, aubergine tarta. Both will satisfy the same basic objective need – hunger. Both will purchase food that is in no way trademarked. Still, would it be OK to say that chips and aubergine tart do not communicate anything on their own?

Even if the item you sell has no large logo on the packaging, it still communicates a lot on its own. This explains why it is so important to ensure coherence of the customer experience from the very beginning. If a bank offers private banking services, it must attend to the prestige of not only its accounts but also the standards of customer service that must correspond to the gravity of e.g. opening a deposit account worth several million dollars. And the other way round, if your brand targets the audience that appreciate economy and minimalism, excessive extravaganza may discourage your potential customers who will quite likely assume they are tricked into overpaying for the image-generating packaging.

3. Good advertising must be a living experience

Baudrillard introduced the notion of ‘simulacra’. He maintained that the contemporary culture has created phenomena which loom somewhere at the border of the abstract system of signs and real-world entities. Disneyland is a good example of the concept: it is, theoretically, ‘fake’ and all attractions one finds there are pure simulations of a fairy-tale reality, but on the other hand, tourists visit the place and spend time there in a manner which is absolutely real.

Conclusions seem obvious: successful advertising must drop banners and escape the TV screen, involving the consumer in a real experience instead. Real-time marketing makes a particularly good use of the idea as it relates abstract advertising content to current affairs that happen in the real world. A good example is the Oreo case: when a few years ago a power blackout marred the Super Bowl finals, Oreo’s marketing team took minutes to produce an apt illustration of the event. It is still advertising yet… apparently a bit more than just that.

SALESmanago

is a Customer Engagement Platform for impact-hungry eCommerce marketing teams who want to be lean yet powerful, trusted revenue growth partners for CEOs. Our AI-driven solutions have already been adopted by 2000+ mid-size businesses in 50 countries, as well as many well-known global brands such as Starbucks, Vodafone, Lacoste, KFC, New Balance and Victoria’s Secret.

SALESmanago delivers on its promise of maximizing revenue growth and improving eCommerce KPIs by leveraging three principles: (1) Customer Intimacy to create authentic customer relationships based on Zero and First Party Data; (2) Precision Execution to provide superior Omnichannel customer experience thanks to Hyperpersonalization; and (3) Growth Intelligence merging human and AI-based guidance enabling pragmatic and faster decision making for maximum impact.

More information: www.salesmanago.com

Follow

Follow